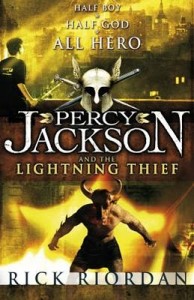

Yes, I know: where have I been these past six years?? It is the unforgivable truth, I had not yet read Percy Jackson. But now that I have at last, I thought I’d devote a Sunday review to the first volume, Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief.

Yes, I know: where have I been these past six years?? It is the unforgivable truth, I had not yet read Percy Jackson. But now that I have at last, I thought I’d devote a Sunday review to the first volume, Percy Jackson and the Lightning Thief.

Percy Jackson is the story of a twelve-year-old troublesome kid who turns out to be the son of sea god Poseidon. In a self-aware americanisation of Greek mythology, the book resolutely plays on the motif of hybridity – hybridity of the hero in a world that is in itself a multicultural hybrid, hybridity of genre, hybridity of time and space – to create an entertaining story that is not actually that simple, and which says a lot about how America perceives itself.

American culture is truly the focus of the book, and the displacement of Greek mythology in its heart allows for an interesting exploration of its current mixed feelings about itself.

It is a culture which, ideally, idolises the power of the individual, as illustrated so often in superhero comics. But it is also a culture which, in practice, fails to recognise ‘true’ power, clinically seeking to stifle it instead. In what is one of Riordan’s smartest inventions, Percy the demigod has been diagnosed with ADHD and dyslexia, both of which betray his godly origins. This denunciation of the medicalisation of misfits is a nice symbol of a society which leaves its children’s abilities untapped.

Similarly, the book oscillates between a sometimes tiresome enumeration of bland American clichés (especially food, particularly processed and unhealthy), associated with the necessary road movie sequence, and a return to the wild furiousness of Ancient Greek mythology. This also gives rise, structurally, to a book modelled on the episodic form of the epic narrative, but in which most of the episodes are strangely reminiscent of a Goosebumps opus. The US in Percy Jackson is a sleeping society – one that has to look to the past for thrill.

In short, Percy Jackson is an amusingly ambiguous glorification of the US as the ‘heart of Western civilisation’. As the text patiently explains, Greek gods move Mount Olympus to wherever ‘Western civilisation’ seems to be at its peak; nowadays, obviously, it is the US. Riordan seems to clutch at this unquestioned ‘fact’ like a drowning man – and despite his faith in America the Beautiful, the whole book makes the US sound in fact like a civilisation in decline.

Medicated children, the flavourless reality of everyday life, a society which glorifies the famous individual but, left without true heroism, has to borrow it from ancient myths – this is Riordan’s America, and this is the enduring image of national identity that the reader is left with.

It is a lively, action-packed, fun book. The central trio is as attaching as it can be, and the joy of recognition of the many mythical creatures and characters makes for an entertaining read for the Greek mythology enthusiast. But it is, above all, a disturbing cry for help from an America faced with its own decadence.

by Clementine